Saturday, April 20, 2024

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

Towards Ending Ableism in Education

We are often told that "everyone is unique", "we are all different" and other such statements meant to convey that we appreciate the differences that make up our community, but when those differences require effort, funding or change, society tends to show a rather different face. In Hehir's "Towards Ending Ableism in Education" he confronts us with the reality of disabled people's educational opportunities. One parent of a disabled student remarked that "while disability is not a tragedy, society's response to disability can have tragic consequences..."

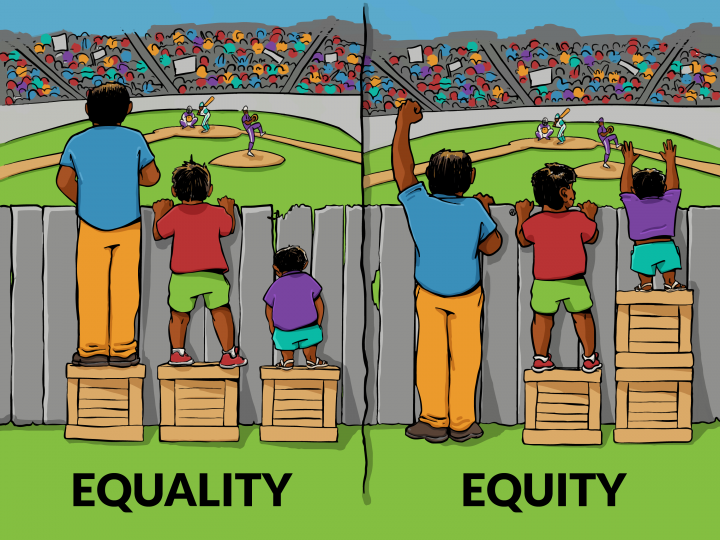

Having to fight for standard educational opportunities is something that any parent of a disabled child must anticipate. Sometimes schools will balk at providing necessary accommodations because of funding, sometimes it is seen as "not fair" (having talk-to-text technology for dyslexic children but not others for example) and sometimes popular ideas and ideologies over-ride effective research based strategies - the move away from ASL to oralism in the deaf community for example. But student rights are protected, and every student in the United States has the right to a Free and Appropriate Public Education, in the Least Restricted Environment. The practical application of these laws is often left to the parents to figure out on their own however. The parent may need to provide diagnosis evidence and petition the school to provide resources, which often relies on the parent to have good knowledge of the legal educational system. It also relies on the parent being willing to label their child. Parents of a child with a learning disability may not want the stigma of an Autism Spectrum Disorder on record, but without it, the school is not obligated to provide any additional services. Hehir noted that not wanting to label children with disability "undoubtedly reflects the deep stigma associated with disability in our culture."

In the video "Examined Life" with Judith Butler and Sanaura Taylor, Sanaura Taylor commented that "a walk can be a dangerous thing". She was born with a syndrome with fused her bones and she uses a wheelchair to take a walk. Her disability is visible and can make her vulnerable. She commented that her disability has the ability to make others deeply uncomfortable. She asked "at what point do we become non-human?" Hate crimes against the visibly different are all around society, and the murder of a young man in Maine simply because he walked differently was highlighted. Sanaura Taylor's point was that society will often help those it deems deserving of help. Why is it a struggle to help those with disabilities? Are they undeserving? Are they not really human? It is a question we should continuously ask ourselves as educators. If everyone is deserving of a Free and Appropriate Public Education, why is it such a fight to get one?

Hehir referred to the Deaf community that had long established itself in Martha's Vineyard. The Deaf community there used ASL and was a highly educated community with many of its members holding heading roles on the island. Literacy rates were high. Though both history and recent research it has been acknowledged that "developing the manual language (ASL) in deaf children is the foundation for literacy and for later educational and occupational success." However, as a focus of oralism and lip reading become popular, this focus on developing manual language declined...alongside deaf literacy rates. The focus on "be like us!" harmed the deaf community and their educational opportunities. Ableism at its worst.

Hehir argues that acknowledging the different abilities of individual people and finding ways to still provide appropriate education and occupational opportunities is our duty as a community. And if we don't, we need to ask ourselves why? Perhaps we don't see everyone as being completely human and deserving. How does that make you feel?

Sunday, April 7, 2024

Literacy With Attitude

Patrick Finn writes a condemning piece in "Literacy With Attitude", as he looks at the style of teaching we give different economic classes in the United States of America. He takes the position that, depending on your economic class, you are either taught "Empowering Literacy" or "Functional Literacy". Empowering Literacy tends to lead to positions of authority and leadership. It encompasses not just the rules, but the reasons and the history and the connections to real life situations. Functional Literacy is about domestication; being productive but not troublesome. It encourages obedience and rules, but not questions and creativity. Finn claims that literacy is being taught in ways that limit students based on their social and economic class. If you are in a poor school, you are being taught what you need to know to live, but not lead.

Finn draws off the studies of Jean Anyon, who studied 5th Grade classes in 5 public elementary schools from different economic situations. She looked at what was taught, how it was taught, as well as the language and attitudes of teachers in those schools. She noticed pronounced differences in the way students were taught, and labeled schools with themes to sum up the experience. In the poorest schools, the theme was Resistance. Resistance to learning, education, rules, teachers, even opportunity. In response to that resistance, the teachers were dictatorial and focused on a product, not on understanding. At the other end of the spectrum was Excellence. Students coveted, sought out and expected excellence. Teachers encouraged creativity, exploration and independence. A pdf of Anyon's study can be found here

As a teacher I have experienced the shock of culture difference when adjusting to a new school. I taught at a school that would fit nicely into Anyon's category of "possibility". Students had at least one working parent, but would be middle class for the majority. These students saw possibility in education, and for the most part accepted the rules and traditions of the schooling experience. We may have trended towards the Individualism/Humanitarianism category, but teaching methods were quite rule based and traditional. As I transitioned from that experience to my current school I received the shock of my life. I found myself in a teaching situation that reeked of resistance. I had to rethink all my teaching strategies because what worked in my previous situation did not work in my new situation. When reading this article about teachers saying the kids "can't handle" group work, I thought they were quoting me. Interestingly, those same students, 3 years later, have stopped resisting and are open to the possibility of what I have to teach. Their social and economic status' have probably not changed, but we have built relationships and shared experiences over the years. I have become a steady fixture in their lives and instead of resisting they now choose to participate. Because of this I have been open to less rigid lessons which allow more freedom of expression and creativity. We have a sense of shared expectations and trust now. So is it a student's low economic status that leads to educational resistance? Or the lack of trusted relationships? Why are they intertwined? I certainly never told my students to "shut up" or doubted their intelligence as reported in the study, but I did realize that I had to teach them social skills before music skills. Mutually we had to learn to trust each other before we could learn from each other. This article made me revisit that transition and view it will new eyes. Your teaching style will always change based on the needs of your students, but should their economic status guide your classroom? I would hope not.

Teach Out Project Slides

Teach Out Project Slides

-

Armstrong and Wildman assert that "Colorblindness in the new Racism" in their article, and follow Johnson's argument that soci...

-

Alan Johnson argues that before change can happen, we must acknowledge and name the problem we seek to change. The difficulty in naming a pr...

-

Our society and the culture we live in can create miracles. We can drive our energy towards landing a person on the moon. We can create pub...